I started with:

You and I met on Twitter. When I initially read your profile, I thought we'd connected because we're both writers. But one of the first things you mentioned to me was your passion for vintage beefcake. That's obviously a passion I share with you and the fans of my vintage beefcake blog.

Maybe that’s because I am vintage beefcake. I grew up in New York, and I vividly remember the windows of the porn shops on 42nd Street, long before Disney came along. I remember the men in hats, smoking, the silences, sneaking in and getting kicked out because I was too young. You couldn’t show dick at the time, so everything was idealized, classical, pillars, posing straps. And of course this imprinted itself on my erotic consciousness in a way that the million-times more graphic porn of today can never equal. In vintage beefcake, there was mystery involved; you had to call on your imagination, write the story yourself. Just where did those crumbled pillars come from, anyway? On which mountaintop did that healthy male frolicking take place? What vanished civilization was this?

You wrote that the older gay male characters in your first novel, These Things Happen, enjoy vintage beefcake, while it's of little interest to the gay teenager in the story.

That might be because Theo (the kid you reference) can just go online and see anything he likes, all the time. My old guys (all of them younger than me, by the way) had to connive, be furtive, worry about being caught, sweat a little. The way it should be. Theo’s parents would probably help him write a punchy Grindr profile; God forbid they should seem to be disapproving or intolerant, even if they actually are—which is one of the book’s subjects. I wonder about straight kids and gay kids … if the availability of the most graphic sexual images takes away some of the thrill of discovering sex for yourself. I hope not.

You are an Emmy and Peabody award-winning television writer, director and producer. These Things Happen is your first novel. It is a coming-of-age tale about fifteen-year-old Wesley Bowman in New York City. After living much of his life with his mother and her husband, he moves in with his gay biological father and his life partner. What is it about this story that made you want to tell it as a novel?

I always wanted to write a novel, and was always afraid I couldn’t. I don’t know why. I started out writing fiction, and was in The New Yorker at 21, which might sound glamorous but made me self-conscious and held me back. Then, happily, I did write a novel. The material led me to the form; I wanted to be able to enter the consciousness of an assortment of characters, to be with them on a moment-to-moment basis, where they were experiencing what was happening both externally—which is what you can do in drama—and internally, which is what you can do in fiction. I played with the material in different forms, and in the end it seemed it might work best as a book. Particularly, as I got into the heads of two characters who are, I suppose, at least on the surface, hard to like. I’m talking about the mom and dad. Being with them, sitting with them, listening to them, I came to respect them, even love them. And I hope readers can do that, too. Without spoiling anything, the dad is, for me, the key character; he comes the longest distance. It might seem tiny, at first, but it’s immense for him, and it pays off (that is: I hope it pays off) in the book’s final moments. And I can say, without spoiling anything, that until I wrote those moments, I had no idea what would happen in them. There it was. I thought “So that’s who you are. I would never have guessed. Thank you for letting me see that.”

Each chapter of These Things Happen is told in first person by one of the characters. There's Wesley, of course. And his best friend, Theo, who comes out of the closet while giving a speech at school. And chapters by Wesley's mother and her current husband. And by Wesley's biological father, Kenny, and his life partner, George. As well as chapters by two other characters. Why did you chose to construct your novel this way?

Again, it wasn’t a conscious choice. I didn’t know I was doing it until I’d finished the first section, which is told from Wesley’s P.O.V., and began the next, which is told from George’s. When I first started to think about These Things Happen, I thought I’d write the whole thing from Wesley’s P.O.V.

I was wrong, but I didn’t know that until I came to the moment that ends the first chapter and I felt a kind of click, telling me it was okay to leave him at that point and to go check in with someone else. And that set the pattern for the rest of the book. I wrote until—the click, until the moment where I could leave one person and visit another.

As for the first person-ing, I think I used that as a safety net, because it’s what I knew. The whole long last section, though, is written in the third person. Again, that wasn’t a choice so much as an event, that I witnessed. Maybe I felt more confident at that point. Whatever the reason—I just followed it.

Which character's voice was the hardest for you to pinpoint?

None of them. They’re all me. I used to say on thirtysomething [for which he wrote, directed and produced] I was all the characters, including the house. I’m everyone in These Things Happen, and I only saw that when I was done. I reconnected with an old tenth-grade friend not long ago. I sent him the book, and he told me Wesley was exactly who I was at fifteen. That stunned me. How had I not seen that? Maybe it’s what made him fun to write, though.

Was there a character you most related to? One whose point of you most enjoyed inhabiting?

I loved writing all of them! By which I mean I loved being all of them. They all surprised me, they all knew themselves better than I did. Sometimes when I was writing this book, I felt more like a secretary to the characters than the novelist who was bringing them to life. A writer friend said to me that you don’t write the book; the book writes you. I felt that all the time with These Things Happen.

Two characters are gay bashed in your novel. This terrible event is of course a major turning point in the story. Without revealing spoilers to anyone who's not yet read your novel, what do you believe is the message of These Things Happen?

That’s changed, as I have. At this point in my life, I’d say—none of us can know ourselves, or others, completely. And every now and then, if we’re lucky, these things happen in our lives that show us something about ourselves we didn’t know, something with which we’re not comfortable, and would harshly judge in others. What do you do when one of those moments comes into your life? Do you hide from it? Do you fall apart? Do you acknowledge whatever it is you’ve seen as an integral part of who you are? Can you let yourself be loved for everything you are? I’ve written about that a lot over the years. I never know I’m doing it. But it seems to be a magnet for me.

I mentioned earlier you are a television writer, director and producer. In fact, you've worked on some of the most iconic, generation-defining shows of the last 30 or so years: thirtysomething, My So-Called Life, the American version of Queer As Folk, and Armistead Maupin's Tales of the City (the 1993 PBS television adaption of Maupin's first book in the Tales of the City chronicles)—just to name a few.

And those are the ones I talk about! There were lots of duds and clinkers in there, as well. Lots of movies that didn’t get made, pilots that didn’t go to series. But that’s anyone’s career. I feel lucky to have worked on a couple of projects that impacted people’s lives. When the book was published, I worried that people would say, “Oh, he’s just some slick hack from TV,” but that didn’t happen. Wherever I went, people told me their favorite thirtysomething episode, or how sad they were when My So-Called Life got cancelled after its first season, or how important Tales of the City was to them. I don’t think a week has gone by in the twenty years since it was first on that someone hasn’t told me that it changed their life. I had an operation ten years ago, and when I was (briefly) in the ICU, I saw my male nurse had one of the Tales books in his bag. When I told him I’d worked on the show, he said to me: “Those books saved my life. Now let’s save yours.”

The first television show you wrote for was Family in 1978. How did you become a television writer and producer?

I started out, right out of college, writing for The New Yorker. I thought that was going to be my life, but it seems my life had ideas of its own, and laughed at the ones I had. I wrote a spec script for Family while I was working on a cruise ship as a singles host. I sent it in cold, didn’t hear anything, and forgot about it. A year later, I got a letter, because they had letters, then, telling me they wanted to buy it and bring me to California. So I went and, it seems from the available evidence, I stayed. One thing leads to another, some things don’t lead to anything. But enough things lead to other things so that, finally, you’re in your story, and you realize that nothing happens for a reason. Things just happen. Which is maybe what I should have called my book. Or, maybe, Things Just Happen, And Sometimes You Get A Little Lucky. I feel that way.

|

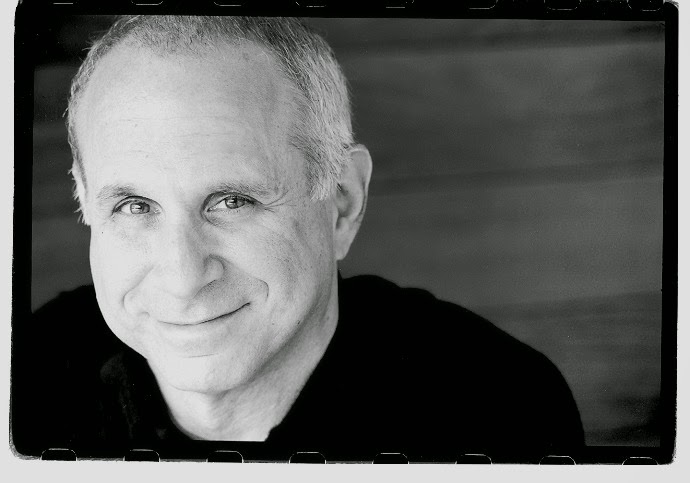

| Richard Kramer (Photo: Beau Deshotel) |

I love this question. It’s caused me to look back and remember that it was the producers and executives who were twenty years older than me who made it comfortable for me to be out, and my peers who made it uncomfortable. Of course, you always collaborate a little with the discomfort of others, without realizing you’re doing it. That’s true to this day. How could I be more out? And yet it’s still not easy for me to jump in and say, “I’m gay, by the way.” I do it, of course, but I always feel a little worried, even a little ashamed, and then I’m ashamed of being ashamed. Some of which is woven into the book, most notably, in the character of the dad. Will I ever fully get over that? I doubt it. I don’t think that’s the goal. The goal is to see it; that’s how you start to get free. Note that I say start.

In the 1990's, I was blown away by My So-Called Life, which stars Claire Danes as a 15-year-old dealing with her life at home and at school. Why do you think the show has retained its popularity?

Well, she’s got a lot to do with it, of course. I remember the day she walked in for the audition. None of us even knew what to say. We were almost afraid to say yes to her; she was so far outside the range of the typical television teen girl. She hardly even seemed human. But she was magic, and she caused us to rethink the whole show, to respond to what we saw in her, to mirror her rawness, her authenticity, her elegance. She came with a ladder which we all had to climb. And Winnie Holzman’s script, of course, was perfect. If it hadn’t been so good, I don’t think we’d have drawn Claire. And the show would have been just another teen show. I have a theory that if you write it, they will come. Write it right, that is. I believe the right actor finds you. That was certainly the case with the thirtysomething cast. And the Tales of the City cast. I don’t think it was the case with the Once and Again cast, although there were wonderful people in that, of course. As for the show itself, and why people love it—again, I have to nod to Winnie Holzman, who, of course, went off to write Wicked, which was no accident; Stephen Schwartz was a huge My So-Called Life fan, and could tell that Winnie had a rare understanding of the inner lives of teenage girls, witches and otherwise. And she led the way for us. She set a very high bar. Also, we did nothing to make it seem of-the-moment. We didn’t have a Teen Advisor; we wrote ourselves. My So-Called Life as a Middle-Aged Jew; that’s what should have been the title of the show.

In addition to both these projects being centered around teenagers, what do My So-Called Life and your novel These Things Happen have in common?

They’re both about authenticity, I think. Angela Chase and Wesley Bowman both fiercely insist on it. They’d make a nice couple. I hope they meet at Brown.

I am a massive fan of female leads in television and film. I happily binge-watched the entire first season of Bitten the day I found it on Netflix. I love watching Claire Danes now in Homeland. I miss Buffy and Veronica Mars. There's a dearth of female-lead dramas and comedies on television and at the movies.

But that’s changing, right? I love Scandal. I don’t love Orange Is The New Black, but I think I get why people do.

I enjoyed the British and American versions of Queer As Folk, which centers around gay characters living in small towns next to major cities, where many gay characters typically appear in fiction.

What drew you to this television project?

The British version drew me. Period. There was something so muscular about Russell Davies’s story-telling. I’m not a fan of the American version. Maybe because I got fired from it!

As you know, I live in San Francisco. I was born here. I am deeply in love with almost all the characters in Armistead Maupin's Tales of the City chronicles.

How did you end up working with Maupin on the television adaption?

It goes back to ten years, at least, before the show went on the air. When I first met Armistead, I think that only the first two books had been published, maybe the third. When we first worked on it, it was going to be a half-hour comedy. We called it Mary Tyler Moore For The 80’s. I wrote a script. And now, neither Armistead nor I have any memory of that stage of the experience! I ran into someone recently who told me she had been the producer of that early version. You could have fooled me!

What message would you like your audience to take away from These Things Happen and the TV shows you've worked on?

None. On the TV shows, we ran in the other direction if we saw a message heading our way. It’s the same with These Things Happen. You throw some characters together, you watch what they do, you see what they want, and how they do or don’t get it. [Film and television writer, director and producer] Ed Zwick used to say the only message he wanted the shows to impart was to keep your hands inside the bus. The message is made by the audience.

These Things Happen has been picked up by HBO and HARPO Films for development into a half-hour comedy TV series. Richard Kramer is currently writing the pilot.

No comments:

Post a Comment